Dogu

Bankov

Dogu

Bankov

1884-1970

An artist's significance is usually measured by the creative product of

their life time,

plus their ability to present ideas to influence their environment. To

this Bankov never came close; with only three exhibitions before 1960.

Furthermore, not one of the exhibitions received anticipated attention,

despite Baden Baden in 1927, which made him the victim of some very harsh

words and ridicule from the press.

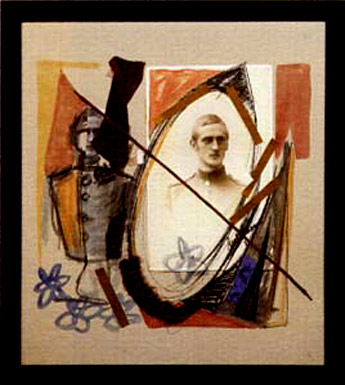

1a,b. To leave the country

73x64, 53x39,5. Not dated. Unsigned but during the years in the Russian Museum in New

York it was accompanied by an attestation by Dogu Bankovs sister, Vera

Bankova. Photographs from the exhibition in Baden-Baden shows this work mounted together with the photograph of the little boy as we

have chosen to do here.

However, what wasn't mentioned was that a series of works were sold from

the exhibition - three of which were bought by The Baden Art Museum. This

particular collection of Bankov's work is primarily due to the inexhaustible

Amchiel Goldstein, Bankov's friend of many years (if anyone could indeed

be called a friend of the shy, recluse Bankov). Goldstein - originally

known as Vladimir Schukschin - came from Kazan in Russia. Partly due to

the war in Europe, partly to his Jewish connection, but also on the grounds

of pure economical interest, Goldstein lived an unsettled life until his

death in New York in 1954. Since Goldstein was one of the founders of

the small, but very interesting Russian museum in New York, a great deal

of his collection entered the permanent collection. Even today, you can

see works by the Constructivists and the 1920's Avantgarde - for example

Alexandr Scheyenkow, the brothers Mikhail and Abram Weksler, and Vladislav

Strzeminski (whom Bankov greatly admired and was partly influenced by).

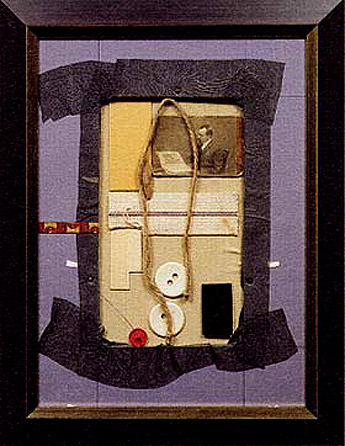

3. Black theatre

60,5x53. Title made by Amchiel Goldstein around 1950. Unsigned. Not dated.

Probably

this work has been made in the mid-1920s but as so often in Bankovs works

elements are added or taken away over the years. In this work there are

many loose elements -including the photo of the four officers (of which

we know for certain that at least one of them was Bankovs lover. The fact

that the photograph falls around in the picture for every new mounting

could perhaps give the viewer some interesting ideas - which we will not

mention here.

After Goldstein's death around seventy works by Bankov were removed from

the

museum's permanent collection, and then in 1973, three years after Bankov's

death, the works were returned to the Goldstein family. The reasoning

at that time for the removal and return of Bankov's works, was that due

to his Bulgarian identity, the presence of his works in the Russian Museum

proved difficult. Furthermore, there were those who considered Bankov

a Dadaist, which was not a profile the museum appreciated. However the

advantageous result was that the works were returned to Europe by the

Goldstein family, in particular Anna-Eliz Janco-Mehlik who placed a number

of the works in Bulgarian museums, and also this important collection

in The M.K. Ciurlionis National Museum in Kaunas, Lithuania.

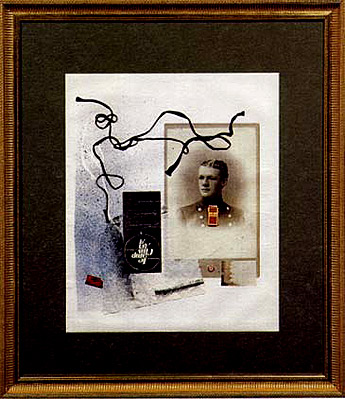

7. I am beginning to understand

101x87. Unsigned. Dated 1925 on the back.

But according to some of Goldsteins

letters a few formerly incorporated elements were later omitted. The title is

questionable as, first of all, it is only mentioned in Goldsteins letters from the

1930s, secondly; understand what? Bankov was probably going through a

personal crisis as no work from Bankovs hand dates from the years between

1917 and 1921. A photograph from Bankovs almost empty studio in 1917 shows

this work - unfinished - on the wall surrounded by black cloth.

Perhaps the most disappointing aspect of the transfer was the loss of

almost all of Goldstein's notes on the works. From alternative sources

and photographs found after his death in 1970, it seems that Bankov worked

for his own amusement. A number of photographs on exhibitions and a few

amateur snapshots taken in his studio reveal that some of the elements

from his collages reappear in much later works – which largely indicates

that earlier works were destroyed. Nevertheless, we can see that the elements

in the collages, and especially the incorporated photography, has a strong

personal connection. People who in one way or another had some form of

personal connection to Bankov, pop-up continuously in the photographic

content of the collage. Then later they risked being removed, as the relationship

between the subject and Bankov changed.

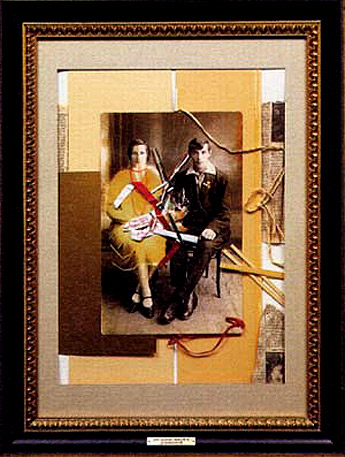

13. Party for Stage

13. Party for Stage

85x73. Unsigned. Almost invisible dated 1950 at the back.

For once we know that

the title is Bankovs own. The actor portraied is Pierre St. Luchien-Aubry,

well known in pre-war Paris. As he is included in a number of Bankovs

works we have reason to believe that Bankov was more than a little fascinated

by him. However, this came to nothing, but he is mentioned on a few occasions

in letters to Vera Bankova as Miss Aubry (!) and described as a kind of

party-lion, hence the title.

Much

of the latter indicates that Bankov could never have been a part of the

Dadaist milieu. The Dadaist's cold approach and opposition to society

at large will always be far removed from Bankov's love of the narrative

and sometimes almost private world of presentation. In fact, seen in the

light of the general role of the artist, who supplies works for public

presentation, who personally and economically builds up a career - even

if it is in the Dadaist spirit of protest and opposition - one could question

whether Bankov wanted to be an artist at all.

Today when the few museums and collections owning Bankov's art define

the work as Dada, the definition is based mainly on the material content

of the collage and the time-span of the early experimental works. We know

Bankov met Tristan Tzara, a Rumanian who was one of the founders of Dadaism,

at least once. However, as yet, there has been no indication that this

meeting was particularly successful. The poet Tristan Tzara's statement

that "The most important is solemnly bound to the unknown" is

hardly compatible with Bankov's fondness for personal narrative.

20. No Title

79x60,5. Unsigned. No date.

The Bulgarian-Jewish writer Atanas Castmann was married

to Bankovs sister Vera Bankova for less than a year (1931). Atanas Castmann

was a great admirerer of Karl Liebknecht and this picture was presented

to Castmann as a gift. Bankov rarely showed or presented his art work

to anyone but Castmann remained a friend until Castmann’s death

in 1945.

Perhaps Bankov would have felt more comfortable with the ideas of Hugo

Ball, but after the 1st World War when Bankov visited Zurich, the Cabaret

Voltaire, which Ball started as the Dadaist's first rendezvous, was already

closed down. Ball had stepped down for the true leader Tzara, supported

by the brothers Marcel and Georges Janco. It is difficult to speculate

the consequences on Dadaism if Bankov had arrived earlier in Zurich and

participated with his more personal, softer approach, but the answer lies

as much in his personality.

Bankov's expression was almost naive, he was in no way a leader and took

little pleasure in presenting himself as an artist, neither to the public

or colleagues. However, we do know that Ball and his wife Emmy Hennings

did see some of Bankov's works, because in a letter to Bankov in 1923

they write enthusiastically about his collage and wish him luck with his

oncoming exhibition in Baden Baden (This exhibition was, as we know, delayed

and did not take place until 1927, when Ball was long dead. None of the

Dadaists were present or mention the exhibition at all).

25. The Housekeeper

82,5x62,5. Unsigned. No date. Purchased by Ciurlionis Museum in1999.

Bankov himself

could never afford a housekeeper but this lady was from a family living

close to Bankov in his Sofia years. The photo Bankov took on her wedding

day.

Bankov's income came almost entirely from portraiture; unsigned watercolours

executed on commission for very little money. Or it was photography, also

made to order and without exception unsigned by the photographer. We don't

know how he began with photography, but it can perhaps be linked to his

friendship with the

Bulgarian Princess Evdokia who was a keen amateur photographer. It is

worth

mentioning that this friendship made difficulties for Bankov when the

princess was shot in 1944 and new rulers took over. Even in 1961, when

Bankov was awarded The Kyrill and Metodius Medal for Culture, his friendship

with the princess surfaced and he prepared to leave Bulgaria for good.

A couple of years later he settled in Budapest, but the past few years

had disappointed him, he failed to learn the language, had little contact

with his homeland and little sympathy with Hungarian culture. Bankov felt

lonely and uninspired. Today, there are very few works from this period,

and those which did emerge after his death display a strong influence

from American and British Pop-art. Such art, even in relatively liberal

Hungary, could create great problems for the artist.

14. Bashful Men and

Ship

36x46. Unsigned. No date but completed in Budapest as late as 1964.

The relatively few works from his Budapest-years are almost all influenced by British Pop-art which could indicate that it may date from

just after WWII - when Bankov tried to do works that could reach a greater

public. As so often before Bankov gives small hints of his view on military

life and society in general.

What is Bankov's significance for us today? Art-historically, he is interesting

due to his connection with Dadaism and the Russian Constructivists. Bankov's

art creates curiosity concerning concurrent events in greater Europe.

Even in his earlier work from Paris one can see a unique and individual

style. Could this have come from the academy in Sofia and, if so, what

became of his fellow students? Was he alone? Not likely, but this could

be the beginning of a new and exciting journey through 20th century art

history.

Dr. Bernhard Hölchner

Baden Art Museum