Ian

Campbell writes about Heri Dono:

Heri Dono: installation, technology, presence and absence.

.

Heri

Dono’s art is a multi faceted inquiry into the essence of the artist

as ever-present creative force. His practice transcends the different

disciplines as defined by western academic approaches. His subversive,

innovative, and transformative zeal is unified in a single approach that

is centred on cultural engagement. As an artist, he can combine self-expression

and a collaborative spirit that fuses performative aspects of his work

with gallery installations. One way to explore the issues of artistic

and collective identity as engendered by Dono’s work is to examine

his use of installation as a creative medium.

Installation can be defined as a presentation conceived for a specific

interior that seeks to physically dominate the space. The intent of the

artist is to allow the viewer to actively engage with the space and its

contents, at times more strongly influenced than others (particularly

in the use of sound and moving images). The aesthetic of the installation

is often presented self consciously as a temporary occurrence. This points

to the intimate connection between installation and performance art.

Key figures in the growth of installation in the postwar period strove

to integrate other mediums in a total artwork. Joseph Beuys was notable

for his avocation of an ideal social sculpture that contained political

action as well as performance and sculpture. His notion worked against

the idea of permanence to destroy the power of the modernist art object.

He was opposed to art based on autonomous gestures and believed any person

could be creatively active. His vision was to would allow for an art that

could totally permeate life.

Asian contemporary artists in the 70’s began to adopt these ideas.

Asian contemporary art is uniquely conscious of these concepts. The universal

cultural acceptance of art in cultures like that on Bali enables a closer

approximation of these values to come to fruition. The culture of art

has a major role in the culture, which renders it continuous with society.

Art (particularly performance) makes the temples function and everyone

can have a personal engagement with the artist’s role.

Historical mediums like wayang kulit (shadow puppetry) reinforce the notion

of the value of multimedia presentation. This power to transform reality

is also key in installation art. Often, the artist’s role is to

determine the mood of the viewer by manipulating the gallery space. Also,

there is a loose distinction between living folk arts and contemporary

arts, partly because of the paternalistic perception of Asian artists

as primitive held by the west.

In Asia, there is a constant need to keep

growth and decay in balance. This flux is accentuated in much installation

work where transience is built into the aesthetic.

Heri Dono is a multimedia artist. His childhood interests in drawing and

painting lead him to the very specific desire to be an artist. After studying

at the Indonesian Institute of Arts and exhibited paintings as well as

participating in earth works installation. After his education he studied

wayang kulit. Much of his influence comes from a will to engage with cultural

matters in a humourous way that borders on the illogical. His imagery

is based both on cartoons from the west and on traditional puppet designs.

His interest in animation lead him at an early age to see cartoons as

"’[an] animistic world where everything has soul, spirit and

feelings. In this kind of world, communication has no barriers.’"

He believes the value of cartoons lies in the "…opportunity

to explore the illogical world of the mind." These sentiments are

expressed continuously in his installation art in terms of their iconography

and construction.

In order to communicate this vision of the illogical, Dono must constantly

challenge his own inventiveness. Western writers describe him as a "low-tech

magician". This description combines both of the sentiments that

make his works so attractive: they are humble technically and mysterious

in their "exotic" toylike charm. They are imbued with an adhoc,

provisional appearance that undermines the threatening potential of technology.

Dono perpetuates the prevailing mode of artists working with technology

(Jean Tinguely among others) to make the works vulnerable and therefore

palatable as art objects.

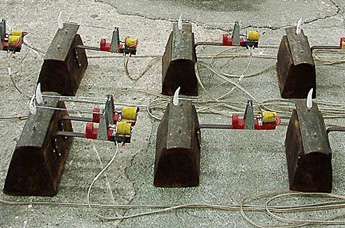

The piece entitled Gamelon Goro-Goro (fig 1) allows the viewer to become

a witness to a series of interrelated processes. These multiple systems

are made transparent to the viewer by the long sections of trailing wires

and the tubs of water draining into each other. A connection is made between

water and electricity reinforcing Dono’s urge to show "the

spiritual energy of electricity". The animism of traditional rural

cultures is brought into the world of science and technology.

While his paintings share a particularly visceral content that can be

seen as political, the installation pieces are somewhat more spiritual.

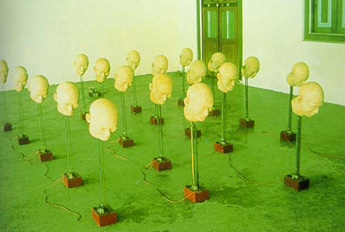

One particularly successful deviation from this is Fermentation of Mind

(fig 2). In this work, a series of Fiberglas heads bob on mechanical cranks

accompanied by tape-recorded chanting. "Fermentation of Mind signifies

the importance of obedience in Indonesian culture… one reason for

Indonesian governments since independence growing into totalitarian regimes."

These concerns extend the systems he is investigating in his work to the

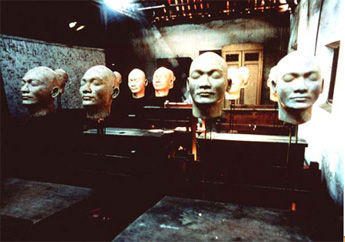

political realm. This is present in other works like Political Clowns

(fig 4) where the disembodied heads rest on skeletal superstructures that

reference the body. These analogs for people critique the use of naturalistic

sculpture historically as reminder of important people. In contemporary

art, like the Fermentation of Mind, art is more likely to be used to elevate

a personal vision of humanity, perhaps even referring to the unamed and

the powerless.

Dono says of installation, "…I think the meaning is not only

in the exhibition, but also in the process, because they employ people

to participate in making the piece. This process would allow the artist

and the non-artist to communicate and bond socially." Much of his

installation work is made with the assistance of a grass roots collection

of people working in appliance repair shops. The unique economic environment

of Indonesia ensures that there is a constant demand for repairing devices

like TV’s and radios that people in the west would normally just

throw out. The meaning that accompanies the resurrection cast off technology

is important to understanding the social implications of these works.

By being part of a human system of labour he establishes the presence

of both the artist and the technologist. Their work is less likely to

be subsumed by the monolithic and authoritative power of commodified electronics.

This helps to illustrate the simplicity that diffuses any threatening

power in the use of these materials. Dono’s work retains the handmade

quality of the handicraft while presenting a vision that is more complicated

than a mere tourist item. In the viewers mind a disconnect forms between

preconceived notions of the traditional and the contemporary.

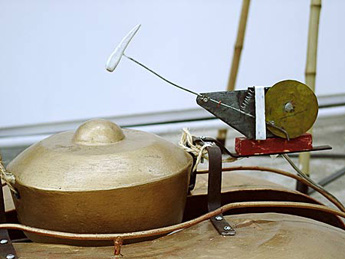

Dono seeks to remind people in the industrialized world of old technology

and to accept differing levels of technology just as he accepts different

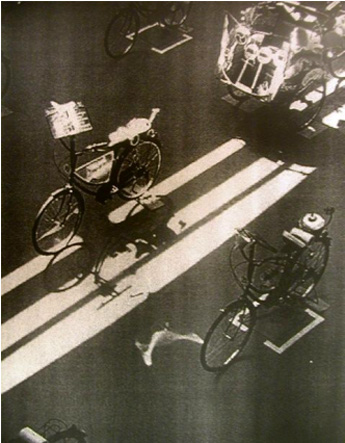

levels of society. In reference to his piece Animal Journey (figure 3)

he says, "Everyday in Yogya, I use a bicycle, and I go everywhere

with it. This makes me think of people, especially the people in Harima

[Japan], because Harima is a ‘technopolis,’ a new city. I

wanted to remind them that the bicycle is still important." This

illustrates how his found materials derive from personal engagement with

his local experience. The symbols of the bicycle or the Gamelon are less

fetishistic gestures of an exotic culture than an attempt at exporting

a common experience to another culture and seeing how people respond.

The implications of Dono’s work as it is perceived in different

cultures shows how technology can be demystified by other cultures that

are perceived as older, and less intent on using it for evil purposes.

This shows the contemporary artist’s constant need to undermine

the sinister implications of technology, replacing them with ones that

are vulnerable and even mocking. Similarly, Dono’s art is invested

with the prescribed meanings of the "primitive" because of his

style of presentation. Dono’s initial invitations to exhibit his

work abroad came from museums of ethnology where he performed his shadow

puppetry. The shift to make art from technological materials may in part

come from the need to be taken seriously as a contemporary artist.

Dono’s main motif in the use of technology in his art seems to be

philosophical as well as practical. Installation brings to the fore the

collision of performance with the gallery venue as it is still appreciated

in the western model (and still permeates the presentation of contemporary

art). This division lies between presence and absence.

Installation is

assumed to be the result of a process, the encapsulation of a time based

project in a physical space. The persistent use of machines is tied to

Dono’s evocation of a cartoon landscape. The implication of automated

pieces like Gamelon Goro-Goro or Fermentation of the Minds is that this

landscape could travel without him.

Generally this is uncharacteristic of a performer who jealously guards

his talents and his image as his only product. Dono’s multi-media

proclivities enable a sense of freedom that allows the use of technology

without it’s anti-humanist allusions. This presence is felt, regardless

of his location. By infusing the works with the animistic it simultaneously

severs it from the autonomous gesture of performance and forces an independence

from the artist.

It is important that Dono responds to his culture both locally and globally.

He can take the otherworldly illogic of cartoons and fuse it with the

medium of gallery bound installation and machine art. This truly postmodern

approach to creating comes from a sincere fascination with invention,

with telling stories and performing that is intrinsic to traditional arts

like puppetry. His identity is not in flux, but his mediums of expression

are, providing him with a large pool of toys from which to amuse himself

and make others think. One gets the feeling Dono is constantly creating,

making sure his form of innovation replicates itself across mediums and

across borders. It doesn’t matter which medium he chooses, the result

will be highlighted by cultural engagement. This is his job.

Illustrations

Gamelan Goro-Goro, 2001, Sound

installation: water vats, gongs, hubcaps, and electric equipment. AWAS!

Recent Art from Indonesia (webcatalog).

http://www.universes-in-universe.de/asia/idn/awas/06/e-zoom2.htm.

Fermentation of Mind, 1994. Installation, mixed media. XXIII Bienal Internacional

de São Paulo (web catalog),

http://www.uol.com.br/23bienal/universa/iuashd3g.htm

Animal Journey, 1997, Flash Art, Volume 33, Summer 2000, p 95.

Figure 4.

Political Clowns, Flash Art, Volume 33, Summer 2000, p 96.

Bibliography

Wright, Astri, "Heri Dono, Indonesia: A Rebel’sPlayground,"

12 Asean Artists, 2000, pp. 86-95.

Lutfy, Carol, "Low Tech Magician," Artnews, October 1997,

pp. 149-9.

Supangkat, Jim, "Breaking Through Twisted Logic," Arts Asia

Pacific, Issue 32, Oct-Dec 2001,

Obrist , Hans Ulrich, "Heri Dono: the Ever Increasing Colonization

of Time", Flash Art, Volume 33, Summer 2000

Obrist , Hans Ulrich, "Hans Ulrich Obrist interviews Heri Dono, 1999",

Chinese-Art.com, ©1999

http://www.chinese-art.com/Contemporary/volume2issue6/interreview1.htm.

Polansky, Larry, "Interview with Heri Dono", ©1997

http://music.dartmouth.edu/~larry/misc_writings/jew_indonesia/heri.dono.interview.html.