The Legend Of Prince Genji

Under the curatorship of Elena Victorova at the Latvian Museum of Foreign Art, we present you with 41 works of which 26 are triptychs by the following artists:

Utagawa Toyokuni III (1786-1865)

Utagawa Kunisada II (1823-1880)

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861)

Utagawa Kuniteru (1808 – 1876)

Tojohara Kunichika (1835-1900)

Utagawa Yoshiiku (1833-1904)

The Story

Genji Monogatari was written around the year 1000 B.C. by Murasaki Shikibu—a woman in the service of the Empress Shoshi. Life in this time period was centered around the imperial court and governed by a strict sense of social hierarchy. Those who were closest to the emperor or members of powerful families enjoyed the benefits of high birth, whereas minor aristocrats living in the outer provinces were often regarded as uncultured and inferior.

The Monogatari chronicles the entire life of the unnaturally beautiful Genji, and ends long after his death during the prime years of his grandson’s generation. Although demoted by his father, the emperor, to commoner status, Genji is destined to become the most powerful man in the nation. His early years are characterized by rash actions and seeking pleasure in women. This lifestyle results in the deaths of both Genji’s wife and lover at the hands of a malevolent spirit, and ultimately, exile. When banished from the capital, Genji fathers the girl who will rise to become empress. Upon his return, Genji attains exalted status and builds his great estate—the Rokujo-in.

The focus of the Monogatari then shifts to the courtships, scandals, and political issues that characterized court life. One central episode includes Genji’s inappropriate pursuit of his adopted daughter Tamakazura. As the tale progresses and Genji becomes ever more powerful, he grows increasingly dependent on his favorite wife, Murasaki. After Genji’s death, the tale moves on to Uji, where Genji’s grandson relentlessly pursues the girl Ukifune. The story ends as Ukifune removes herself from the world of earthly pleasure by taking religious vows.

The Edo

Edo was a time when Japanese art and cultural wealth was at its peak. The city of Edo (modern days Tokyo) grew from an early 16th century walled city into the world’s largest city in the 19th century with over a million inhabitants. The massive influence the capital had on Japan lead to naming the entire period 1603-1867 Edo. For the first time in centuries the country was unified under Tikugawa shogun (feudal lords with hereditary titles), who governed the region with the assistance of daimyo (regional warlords).

With the emergence of a stronger middle-class in Japan, the accessibility of art increased. The nobility were great supporters of culture, and slowly the middle-classes, eager to demonstrate similar values as the nobility, developed a society with a strong desire for art and culture. Art crossed the social barriers and became accessible to large groups of individuals.

When, during Edo, Ryutei Tanehiko published Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji (The false Murasaki and the popular Genji) a 19th century version of the 11th century novel as an illustrated series. The series was an immediate success, lasted 14 years, and became Japan’s first bestseller. Despite Tanehiko’s success he fell victim to the Tenpo-reform and its attacks on the ”morally unsuitable”, and died under mysterious circumstances. His death sent shockwaves through Japan’s publishing houses.

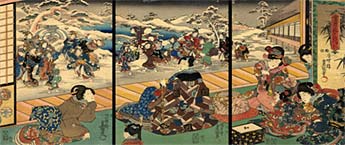

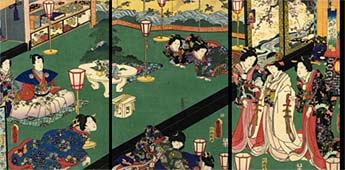

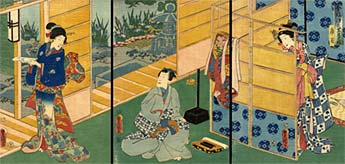

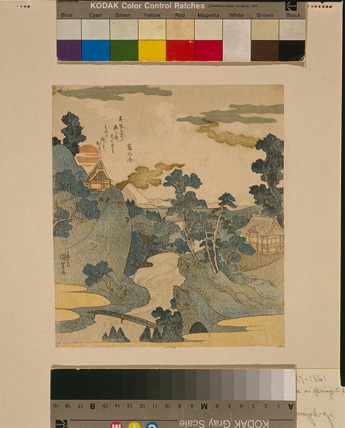

The Genji plots are often love affairs with kabuki-esque elements like an outlawed villain. Landscapes, costumes and manners in these Genji-prints contain more of Tanehiko’s own time than references to when they were written (the 12th century).

The theme itself provided the artists with endless opportunities to portray elegant men and women in colourful costumes in richly decorated interiors. Publishers used expensive formats like in the oban-triptychs and hired the most revered printers of the time. In the Edo several of the persons in the prints were recognizable. Many of them were actors from the Ichimura theatre in Edo. The ban on portraying actors was bypassed with references to the classical motifs in the artwork. The actors, however, were not hard to recognize by contemporary viewers.

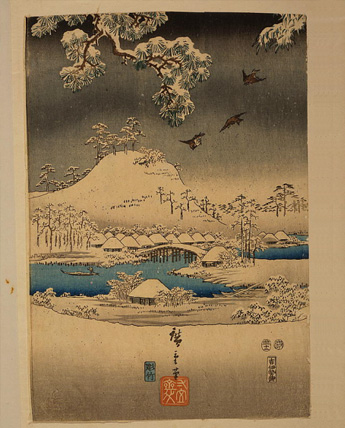

A lot of Tanehiko’s success can be ascribed to the artist Kunisada and his students and followers, who set the standard for these fantastic illustrations. Kunisada’s friend and rival Kuniyoshi also contributed, especially with his fantastic warrior prints. But the style Kunisada had established survived all competitors and became symbolic for the interpretation of Genji-prints for many years. This exhibition refers to a certain theme – images from the life of Prince Genji. Genji in ukiyo-e style was a special and highly popular art form during Edo . The significance of the Genji-e histories are still discussed in professional contexts.

No doubt these stories still contain magnificent woodblock prints by some of Japan ’s most revered artists of the Golden Age.

Utagawa Toyokuni

III (1786-1864)

Utagawa Toyokuni

III (1786-1864)

Utagawa Toyokuni III (1786-1864)

Utagawa Toyokuni III (1786-1864)

Utagawa Kunisada II (1823-1880)

Utagawa Kunisada II (1823-1880)

Utagawa Kunisada II (1823-1880)

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861)

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861)

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861)

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861)

| Next |