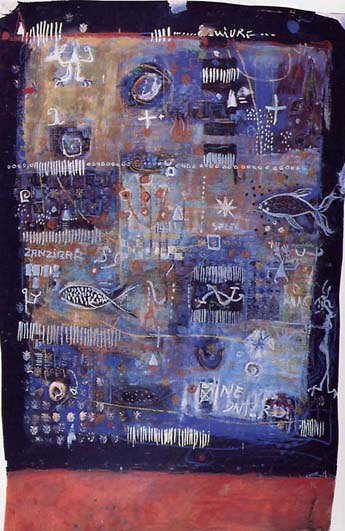

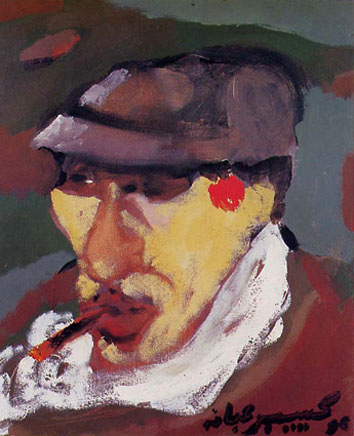

A TASTE OF TUNISIAN FINE ART

A

SELECTION OF TUNISIAN CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS AT GALLERY 3,14

Contemporary Arab Art

By Ibrahim Alaoui

In the Arab world today, the visual arts occupy an important place in

the field of creativity and artistic and intellectual exploration. They

therefore have a major contribution to make to any study of the roots

of creativity in contemporary Arab societies.

The history of painting in the Arab world is only a fragment of the history

of these societies, and evolves in a multidimensional movement where it

is only one part of a whole. That whole comprises not only aesthetic history

but also social history, not to mention the complex relationship between

the producers of symbolic forms and their societies. Unlike the history

of modern Western painting, which was the result of a series of transformations

linked to social revolutions, Arab easel-painting, as a system of representation

which is modern in both its conception and its function, was born, at

the beginning of this century, through contacts with the West which fundamentally

altered not only the social systems of these countries but also the ways

in which Arabs saw the world.

The emergence of this new mode of pictorial expression adopted by the

Arabs is related on the one hand to the establishment of a relatively

autonomous artistic domain (that of the artist as individual creator with

a specific social status), to a market, to an audience, to all those who

are interested in art, and on the other hand to the advent of new mode

of expression and creation: the painting.

Although this artistic domain in the Arab world, with all the relationships

it implies, was established in the early 20th century, it is necessary

to add that easel-painting did not emerge from an aesthetic void. Inherited

forms exist, both varied and essential, to express the cultural capital

with which Arab artists must come to grips. They will no doubt be aware

that their lands, through their creative and intellectual achievements,

have produced a succession of remarkable civilizations which knew how

to spread their influence throughout the world. They are therefore heirs

of a rich and diverse tradition.

This abundant heritage, born of the meeting between pre-Islamic artistic

traditions, on the one hand, and Islamic and Arabic culture on the other,

is reflected in Arab societies characterized by a great diversity of modes

of expression.

It is by considering the foundations of contemporary Arab art in this

multiple dimension that we can most productively investigate the Arabs'

visual memory. Since its foundations are so diverse, and since many elements

and currents have participated in the re-birth of Arab art, its evolution

is far from uniform. However, certain dominant forces have determined

the development of contemporary art in the Arab world.

THE MEETING OF EAST AND WEST

The introduction of easel-painting is linked to the transplantation of

Western political, economic, and cultural influences into Arab countries.

Furthermore, European expansion in the 19th century fostered a growing

interest in the arts of the Orient.

In painting, the Orientalist vogue had its origins in the orders issued

by Napoleon to celebrate military successes in his Egyptian and Syrian

campaigns. Later, the Greco- Turkish conflict and then the colonization

of Algeria resulted in a lasting interest in the Orient on the part of

European artists. The voyages of several major artists to Islamic lands

in the 19th century were certainly determining factor: Delacroix to Morocco

in 1832, Chasseriau to Algeria in 1846, Fromentin to Egypt in 1869, etc.

Their Oriental travels had a multiple significance: at once a historical

and archeological search for the origins of western culture, and an almost

mystical quest for the cradle of religion. These painters also contributed

to the development of pictorial Orientalism, which is to say amore or

less obscure , more or less frivolous search for "the other."

This quest issued from the need to escape from a civilization paralyzed

by 19th -century bourgeois culture, and from the desire to liberate ones

individual subjectivity by giving it free rein. What Westerners sought

in the East was not, moreover, the recognition of their own identity ,

but rather the "Oriental" as Edward said has defined it- an

entity invented by the west, its double, its opposite, at once the incarnation

of its fears and the proof of its own superiority, the flesh of a body

of which it could only be the spirit.

This fascination with the Orient also affected the first European photographers

who set out for the Arab world immediately after the invention of the

camera. Some settled there as early as 1860, such as Felix Bonfils in

Beirut, the Abdullah brothers in Cairo, etc. Film-makers were to follow

them as soon as cinematography was invented - the first projection of

a film by the Lumiere brothers took place in Egypt in 1896. The installation

of Europeans in Arab countries was accompanied by the establishment of

milieus and institutions designed to receive and subsequently to educate

Arab artists. Both intrigued and fascinated by this unfamiliar iconography

and these new inventions, Egypt would be the first Arab country to attempt

to master its language and techniques, and to devote itself to the remaking

of its own image. Thus we witness the emergence of painters, of the first

Arab photographs (notably Mohammad Sadie Bey who as early as 1861 took

the earliest photographs of the Holy Land), and of cinematographers.

THE

EMERGANCE OF ARAB PAINTING

At the beginning of the 20th century, Egypt awoke. Political, social,

and cultural effervescence pervaded every sphere. It was in this propitious

context that Egypt developed its artistic structures. In 1908, Prince

Youssef Kamal created a school of Fine Arts in Cairo, the first of its

kind in the Arab world. Among the original graduates were the pioneers

of modern Egyptian art: the painters Ragheb Ayad, Youssef Kamal, Mohammad

Nagui, and Mohammad Said, and the sculptor Mahmoud Mukhtar. Most of these

artists went on to pursue their studies in Europe.

On returning to their own country, these artists constituted a movement

deeply aware of its role in the emancipation of modern Egypt, and from

1920 on participated in the "Nahda" (renaissance) symbolized

by the statue of the same name sculpted by Mukhtar, a key figure in the

artistic awakening of Egypt in 1928.

From then on, Cairo became the cultural and artistic capital of the Arab

world. The teaching provided by the Cairo Academy of Fine Arts attracted

many future Arab artists, particularly those of Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq.

Some of these artists were instrumental in setting up schools of fine

art in their own countries.

The teaching propagated by these schools, the establishment of artists'

associations, and the proliferation of local artistic outlets powerfully

contributed to the emergence of the first generation of modern Arab painters.

The precocity of this plastic expression, the beginnings of a process

of assimilation during the first half of the 20th century, meant that

Western influence was to be expected, both on the technical and the stylistic

level. However, these artists asserted their ability to represent their

society in their own terms. Their wish at this time was to turn their

backs on the exoticism of the Orientalists and, by returning to their

roots, discover their own authentic voices in the idiom of modern art.

Many pioneering artists manifested the same wish to affirm their own rootedness,

such as the Daoud Corm and Khalil Gibran in Lebanon, Jawad Salim and Faik

Hassan in Iraq, Mahmoud Jalal and Nacer Shoura in Syria, Mahmoud Racim

in Algeria, etc.

Each in his own fashion, these artists were able to build the premises

of an aesthetic philosophy on the foundations of their new artistic activity,

despite the presence of a European artistic community whose ephemeral

success at the beginning of the century, based on a representational and

academic exoticism dominated by genre scenes, was soon to be supplanted

by intellectual and aesthetic revolutions in Europe.

FROM HERITAGE TO MODERNITY

In the Arab world, however, the plastic arts must submit to the vicissitudes

of history. Struggles of liberation, culminating in independence for one

land after another, were accompanied by self- searching and national affirmation.

Ever since the "Nahda", Arab intellectuals had constantly been

searching, each in his own manner, for a form of cultural and artistic

expression adequate to the historical periods to which they belonged.

The desire to create an original form of aesthetic expression impelled

certain artists in Egypt in the 1930's to distance themselves as much

as possible from their immediate predecessors. On the fringes of fine

arts academia, the surrealist current influenced certain intellectuals

and artists who created in Cairo the group "Art and Liberty, "

which from 1937 to 1945 galvanized Cairo intellectual life with its outrageous

activities, at first through the publication of numerous articles and

later through the founding of journals and the organizing of exhibitions.

Ramses Youan, Fuad Kamal, and H. El-Telemsany adopted surrealism in order

to achieve a more liberated style, which seemed to them a decisive step

in the struggle for cultural emancipation and modernity.

Other movements appeared in various counties. In 1949 the school of Tunis

was founded, which marked the birth of modern painting in Tunisia and

nurtured its vigorous development over the following decades. This movement

included painters of diverse origins and styles, who were soon joined

by Ali Bellagha, Yahia Turki, Amman Fathat, Jalal Ben Abdullah, etc. These

artists differed from the Orientalist school in that they favored the

representation of ordinary activities and traditional life. A decade later

the School of Tunis consolidated this vision by finding new ways of representing

both the real and the imaginary life of Tunis.

Much more intellectually engaged, the Group of Modern Artists in Baghdad

was born in the 1950's and immediately involved itself in the cultural

and artistic life of Iraq. It advocated a modernity which was open to

the world but did not renounce its roots. This movement engendered not

only painters but also theorists and critics. It manifestos and critical

writings on contemporary art provided the movement with a solid theoretical

base and the sense of a coherent vision, quite rare in the Arab world

at that time. One of its most observant and perceptive members, Jabra

Ibrahim Jabra, gives a good summary of the group's philosophy:

In their attempt to resolve the dialectic of the old and the new into

a viable synthesis, the Iraqi artists and their defenders opened the way

to a modernism which daringly emphasized its paradoxical nature, which

no doubt explains its peculiar power. It is probably also the reason for

the pre-eminence that Iraqi painting seems to have acquired in the wider

currents of contemporary Arab art.

In the 1960's, the return of certain visual artists to their own countries

after living in various Western capitals also favored the emergence of

new artistic orientations. In Morocco, for example, the painting teachers

Belkahia, Chebaa, and Melehi formed a group at the School of Fine Arts

in Casablanca which led an intensely active cultural life, with the aims

of furthering the contribution of the visual arts to the redefinition

of "cultural identity" and the integration of the arts with

social life. Other painters, as well as writers poets, architects, etc.,

pursued ways in which art could be a vehicle for reflection and culture.

This period in Morocco was notable for the opening of many art galleries,

the creation of cultural journals, and the realization of a wide range

of other innovative projects.

Also in the sixties, Lebanon saw the birth of innovative artistic practices

and the flourishing of numerous art galleries, of which the most influential

was undoubtedly Gallery One, founded by the poet Youssef El- Khal and

his wife Helen. At about the same time, Janine Rebeize and a group of

other Lebanese intellectuals created the Dar- El- Fan, which was destined

to play a major role in the artistic life of Beirut. An exhibition space,

it also became a meeting - place for exchanges between artist, intellectuals,

and art-lovers. The gallery contact, with a wider base, exhibited artists

from other counties in the Middle East, notably Iraq. This new dimension

would serve to give Beirut a pivotal role on the contemporary Arab art

scene.

next page