Lamb

of God

an exhibition by Pippa Skotnes

2004

Catalogue essay:

Pippa Catalogue PDF File

A Miraculous History of the Book

Isabel Hofmeyr

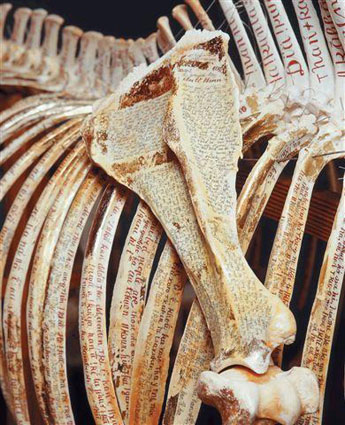

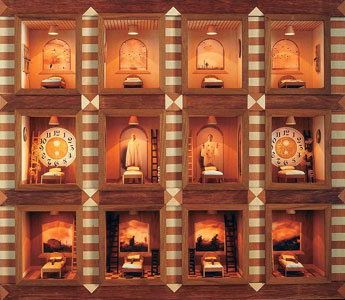

At the centre of this exhibition stand three volumes. Each comprises a

horse's skeleton covered in hand-written texts. Both sumptuous and macabre,

the skeletons - burnished in gold leaf, shod in silver shoes and fully

bridled - draw us closer. The texts inscribed on the skeletons are of

diverse provenance but cluster around three historical periods, namely

medieval and early modern Christianity; the First and Second World Wars;

and finally a group of texts, produced in the 1870s, in the now dead Bushman

language /Xam. Located around the three horses is a galaxy of items: boxes,

reliquaries, cases of objects with textual inclusions, bridled horse skulls,

and multi-media images.

We approach the three skeletons and start reading. There is, however,

no fixed vantage point from which to read. The contour of the bones, the

direction and size of the text determine how we must choreograph ourselves.

We crane and peer, swivelling our heads this way and that. How, we wonder,

are we to read these skeletons, their texts and the objects that surround

them? How are we to navigate the feast of comparison and the extravagance

of relationality implied in the exhibition and its parts?

Like any traveller unsure of where to go, we must seek directions. These

are of course best sought in the texts of the exhibition themselves, since

any text carries with in it an implicit set of 'instructions' for how

it wishes to be read. These instructions lie in its formal arrangement

and rules of composition which will provide us with a set of guidelines

for how to proceed. By heeding these, we might try to make ourselves ideal

readers, to bend and tune ourselves to the imaginative address of these

textual objects.

However, the question of what a text is or might be has been much debated

in literary and cultural theory and much of the intellectual project of

the humanities over the last half-century has been to name and capture

the multivalent nature of textuality. In Barthes' memorable phrasing,

texts are objects of "shimmering depth", "vast cultural

spaces through which our person…is only one passage", filled

with the elusive "rustle of language" (31). At the same time,

much effort has gone into understanding texts as material objects, as

commodities that circulate. To adapt the terms formulated by Alfred Gell,

an anthropologist of the art object, texts as material objects are "temporally

dispersed … moving through time and place, like a thunderstorm"

(226). Other domains, most notably studies of the history of the book

have likewise explored the text as material object. As the doyen of book

historians, Roger Chartier, has observed, any history of the book entails

a three-fold equation: "the text itself, the object that conveys

the text, and the act that grasps it" (161).

However, the theorists cited above have generally emerged from societies

that are hopelessly literate. The everyday practice of textuality around

which much theory shapes itself is consequently thoroughly institutionalized

and most reading practices become uniform and regulated. As a result,

reading becomes semi-invisible and decorporealised. Indeed, at one point,

Barthes notes, almost plaintively "Reading is the gesture of the

body (for of course one reads with one's body)…" (36). The sentiment

in parentheses could only emerge in a context where reading has become

an all but disembodied practice.

In order to capture the full richness of texts and textuality, those interested

in books and reading have often turned to societies in time and space

where reading is not uniformly institutionalized: to medieval societies,

to colonial and postcolonial settings where the technologies of writing

are explored and experimented with on the borders of, and outside formal

institutions (Prinsloo and Breier; Street). These investigations have

illuminated many cases where novel understandings of literacy are at work.

Early African Christian converts, for example, or medieval believers for

that matter acquired literacy miraculously, generally in a dream journey

to heaven or from the Virgin Mary (Hofmeyr, "Dreams"). Jamaican

slaves insisted on being buried clasping their communion tickets which

were believed to be passports to heaven (Curtin 29, 37). In such understandings,

texts circulate between heaven and earth and pose the beguiling question

of what kind of audience might be brought into being by such a path of

textual circulation. As books are baptized in new intellectual formations,

the way they are understood is enlarged, a phenomenon we see in the metaphors

used to describe books in para-literate situations. These include the

book as a flag, as marriage, and as dance (Hofmeyr, "Metaphorical").

In these comparisons, books and their potentialities, are grasped in novel

and distinctive ways and our understanding of texts and their promise

are commensurately expanded.

In this exhibition which entangles so many different times and spaces,

and which poses so powerfully the question of text, writing and material

objects, these novel theories of text and textuality are made vivid before

our eyes. If we heed the horses' instructions, we will learn and experience

a theory of the textual object which takes us beyond much contemporary

thinking on the subject. We will experience texts as multimedia and multilingual

portfolios which straddle the printed and the spoken, image and text,

the visible and invisible world. As a whole, the exhibition maps out the

imaginative boundaries of what a miraculous history of the book might

look like.

To explore this idea further, let us take three types of text distributed

in the exhibition and heed their instructions. They are the bone book;

the rosary; and the archive.

The Bone Book

To comprehend the bone book of the horses, we find ourselves undertaking

forms of reading that are simultaneously modern, medieval and postcolonial.

As modern readers we quickly recognize the bone books as tissues of quotation

and as fragments of other texts. We also respond to their apparent randomness.

From a distance, it looks as though the skeletons have plodded through

some postmodern textual blizzard, fragments of language cleaving to them.

As consumers of contemporary popular culture, we note the information

that two of the skeletons were originally cart horses in Kayelitsha, the

large township outside Cape Town: the 'low' and 'unofficial' has been

recycled as 'high' culture. We smile at the textual parody of one horse

which has a set of bibliographic cards suspended under its spine.

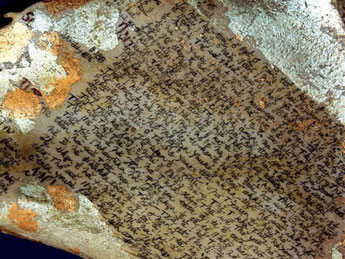

But

at the same time our reading must be medieval. We are, after all, contemplating

the singular and handmade book, transcribed with patient dedication. Is

this act of transcription, as it was for many medieval scribes, a type

of prayer, a textual form that attempts to speak to other worlds? At times,

we cannot read silently but must mouth a word made unfamiliar by the contour

of the bone and so we come to resemble medieval monks, hunched over a

codex and reading in murmurs. Again like medieval readers our senses are

intensely involved: the red lettering, gold burnish and silver enchant

our sight. We hear and feel the horses' tails and the manes, made up of

hair, small bones and curls of vellum. We could be in the world of Augustinian

allegory and enigma in which texts speak allusively or in riddles (or

in St Augustine's words: "wisdom's way of teaching chooses to hint

at how divine things should be thought of by certain images and analogies

available to the senses" [quoted in Brown 253]).

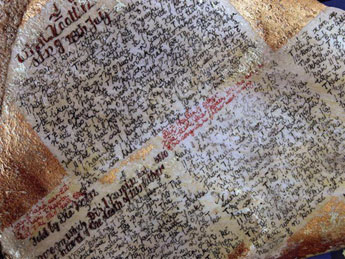

At

moments, the modern and late medieval combine. In several pieces, we encounter

little ampoules, each containing a line from an essay by Stephen Greenblatt

(1996)which describes some of the polemical exchanges between Catholics

and Protestants in the Sixteenth Century and particularly those relating

to the sacramental bread of the Supper of the Lord. What happens if a

mouse or rat nibbles some of the consecrated host? Does he ingest the

Real Body, or does he not? A copy of Greenblatt's article has been cut

into strips, goldleafed and then curled into the ampoules and distributed

across the exhibition. These ampoules look as though they may contain

nourishing elixirs to be consumed, reminding us of the medieval (and later)

preoccupation with Christ's body as flesh and with the idea of the Bible

as a text to be ingested ("Open thy mouth, and eat what I give you,"

God instructed Ezekiel while presenting him with a roll of text [quoted

in Manguel 171]). At the same time, the ampoules spread text across a

surface and point to contemporary preoccupations with the textualisation

of space.

Yet,

at the same time, these medieval and modern practices are thrown into

postcolonial relief and are reconfigured by the presence of the /Xam texts

and the colonial world that they imply. In a medieval context, a vernacular

language would betoken newness and promise. Here the vernacular, its speakers

exterminated, signals language death and the violence of colonial conclusions.

If there is a rustle, it is the rustle of dried language. Yet, the colonial

context also produces newness. Books and literacy, for example, are reshaped

as these technologies of writing are baptized in new intellectual traditions,

many of which are oral.

This

interface has constituted one theme of Skotnes' previous work, particularly

in relation to the Bushman and the /Xam, a group with whose intellectual

and artistic traditions she has had a profound engagement. Her exhibition

Miscast and the edited volume that accompanied it constitute, in Skotnes'

words, a "critical and visual exploration of the term 'Bushman' and

the various relationships that gave rise to it" ("Introduction"

20). An earlier art book, Sounds from the Thinking Strings: A Visual,

Literary and Archaeological and Historical Interpretation of the Final

Years of /Xam Life (1991) investigates in text and image the intellectual

history of /Xam communities. Her two most recent books (Heaven's Things

[1999] and Stories are the Wind [2002]) likewise engage with the richness

of /Xam thought.

One

major source to which she has repeatedly turned is Lucy Lloyd's extraordinary

archive of /Xam narrative and philosophy. These testimonies, songs and

folklore were dictated to Lloyd and her brother-in-law Wilhelm Bleek in

the 1870s in Cape Town by /Xam prisoners from whom Lloyd and Bleek learned

/Xam. The prisoners were released into their care and over a period of

several years, Lloyd and Bleek took down 13,000 pages of bilingual testimony

along with drawings, instruments and objects which today comprise the

Bleek and Lloyd archive, the only substantial collection of documentation

on nineteenth-century Bushman life (Deacon; Hall; Skotnes, Real Presence).

As

Skotnes points out, these /Xam testimonies constitute a complex and multivalent

textuality, a feature which Lloyd understood and attempted to capture

in her form of transcription which generally involved three parallel columns,

one containing the /Xam narrative, one being an English translation and

one being a further /Xam commentary on the narrative. Skotnes comments

(in the edited collection on Miscast whose layout incidentally is informed

by the principle inherent in Lloyd's transcription):

the

stories [Lloyd] was recording were not linear, and neither was the method

of measuring the time frame of their occurrence. To accommodate the qualities

of these oral traditions, she would often introduce a parallel text which

would run alongside the story on the left-hand page. The result was to

give a new dimension to the story, to make the process of reading an active

and mobile one, and to give a materialising life to the notion of //Kabbo,

one of her principal informants, that stories his people told were like

the winds that came from far off, and could be felt. ("Introduction"

23)

Skotnes

continues:

[The

Lloyd archive] has a visual presence, and its structure requires that

it be read, not as a narrative or set of narratives, but as a complex

network interweaving ideas and stories that link one with the other, that

confound a sense of chronology, that throw into doubt one's sense of time

and, ultimately, one's sense of what is real. ("Introduction"

23)

In

this exhibition, these ideas of multiple and interwoven textualities have

been deepened and complicated by the /Xam texts being inscribed on bone.

This principle of text on bone provides an organizing principle of the

exhibition and requires a range of reading strategies.

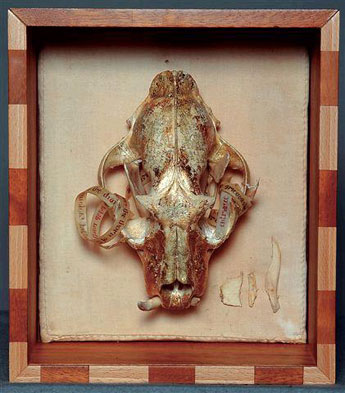

Most

obviously perhaps, the theme of bone highlights the pre-occupation with

medieval religious practice and its obsession with bodily fragmentation,

relics and resurrection, or put in Caroline Walker Bynum's terms, whether

dead parts could again be made whole through redemption (1991). The description

of fifteenth-century devotional painting as a form that put Christ's body

parts "on display for the … beholder to watch with myopic closeness"

(quoted in Bynum 271) could well be adapted for this exhibition: wherever

we turn, we encounter bones - singly, in piles, buried, disinterred, lovingly

presented alongside dried roses, encased in twirls of vellum, displayed

in pill boxes and reliquaries, and clasped in the arms of the priest-figures

who dominate the war landscapes.

At

the same time, the exhibition provides an acute reading of the omnipresence

of bone in southern African history. In the case of the Truth and Reconciliation

Commission (TRC), for instance, a dominant narrative was the story of

relatives desperate to find the unmarked graves of their 'disappeared'

loved ones, murdered by the agents of the apartheid state. In some cases,

these bones were found and re-interred. In others, the bones could not

be located. The testimonies of the TRC constituted a textual mantle or

reliquary over these bones, an endeavour to confer some coherence on the

trauma and to lay to rest the ghosts of the past. The theme of bones and

reinterment has continued to assume importance in the post-apartheid public

sphere (a recent prominent case involved the San woman Saartjie Baartman,

brought from Paris where in the nineteenth century her body had become

a museum exhibit and buried in a public ceremony in South Africa on August

9 2002 [a public holiday: Womens' Day]). These ceremonies around human

remains are all attempts to establish a material continuity with a past

that has been violently torn and, in keeping with African divination,

is an endeavour to make the bones speak. Skotnes brings together text

on bone as an organizing principle of the exhibition and in that relationship,

opens up a new imaginative and visual historiography that draws together

medieval and post-apartheid concerns: can we resurrect, make whole, narrativise,

or confer coherence on that which has been broken and killed?

The

contours of this historiography are further suggested by the three textual

archives that the bone books 'anthologize'. These are texts on medieval

Christianity (including hymns, extracts of Dante on purgatory, lives of

Saints, lists of popes, and controversies on the Eucharist); the First

World War and finally /Xam texts from the Bleek and Lloyd archives. By

radically integrating texts across time and space, this exhibition resonates

with recent revisionist thinking on Empire (Cooper and Stoler). This school

of thought questions the usefulness of older models of 'centre' and 'periphery'

in which everything flows from metropole to colony and instead, asks us

to think of Empire as an intellectually integrated zone in which circuits

of influence travel in more than one direction at a time. In the words

of Gyan Prakash, we need a realignment that releases "histories and

knowledges from their disciplining as area studies; as imperial and overseas

histories…that seals metropolitan structures from the contagion of

the record of their own formation elsewhere" (11). (This same sentiment

has been expressed, in lighter vein, by Salman Rushdie who has noted that

the British do not understand their history because it happened somewhere

else [Clifford 317].) To encompass such ideas, we need a multi-sited methodology

which demonstrates how events are made in different places at the same

time.

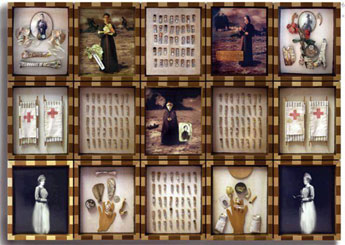

This

exhibition performs these ideas for us in visual terms. One insistent

backdrop is the battlefields of the First and Second World Wars which

explode before us in virtually every image we see. This exhibition reminds

us that this catastrophic encounter affected not only Europe but all of

Empire: troops from across the Imperial world were drawn in; fighting

happened both inside and outside Europe; in some analyses, the war itself

was sparked by Imperial rivalries. As Prakash indicates, the catastrophes

and contagions of Empire cannot be sealed off and demarcated as the business

of either metropole or colony. Imperial catastrophe becomes everyone's

catastrophe.

This

point is underlined by the images that repeatedly splice together different

orders of Imperial carnage: in several images of First World War battle

scenes, we see a foreground of disinterred bones, which at first sight

seems to be coterminous with the First World War battle scene in the background.

However on closer inspection, we see that the brown colour tones of the

foreground differ slightly from the background and we learn that the pile

of bones in the front of the image only recently came to light in a Cape

Town building development and probably comprise slave remains.

If

we are to have an integrated and multi-sited history of Empire, then these

relations have to be simultaneously grasped: foreground and background,

then and now, text and image, here (Cape Town) and there (the Somme).

As other have pointed out (Myers), such a revised history could usefully

be traced through the things and objects of Empire. By tracking the flows

of commodities that coursed through Empire, by documenting the biography

of things and the unexpected routes that they took, we will start to make

apparent the complex pathways and intersynaptic networks of Empire. The

exhibition and its multiple objects put this methodological challenge

to the viewer. How, for example, does an unused roll of Second World War

bandage make its way to an antique shop in Cape Town, and what might we

learn from that story? At the same time, the exhibition plays with this

method: dotted across its space are what look like colonial postcards.

They are however digitally produced. We are asked to ponder the result

and conceptualize what it might mean for a fragment from the present to

be imaginatively and retrospectively circulated via the postal systems

of Empire. In some cases, the digitally produced cards mimic the carte-de-visite

format and bear the name of the photographer W. Hermann who took photographs

of the Bleek and Lloyd /Xam informants and printed these as cartes-de-visites

(Hall). In this case, we are asked to consider the role that a particular

visual genre plays in circulating images, and what it means to transpose

that format from the past into the present with a changed set of actors

within its frame.

The exhibition and its objects also push us towards yet unthought of histories

of Empire that might emerge from its micro-objects. If, for example, we

take the objects of this exhibition like a leopard's vertebrae, a horse

shoe nail, a toy stretcher, and a dried rose, what type of history might

these produce?

The Rosary

When

I first went to Cape Town to see the exhibition taking shape, I had never

used a rosary. In no time, Skotnes produced one from the wonderful cornucopia

of her studio overflowing with every imaginable object - family photos,

animal skulls, wreaths, medical antiques, a stuffed monkey, tape measures,

feathers, dried flowers, parchment clippings, baby shoes, x-rays, relics….

She also printed out a set of instructions, from the Internet, on how

to use it (a text that incidentally recurs in several images in the exhibition).

Using a rosary for the first time, I experienced the complex interaction

of mind, body and text that it demands. The operation has several simultaneous

dimensions: saying a roster of prayers, in a particular order, while touching

the beads to keep track of one's progress, all the while meditating on

the 'mysteries' or events from the lives of Jesus and Mary. The particular

set of events on which one meditates changes according to the day of the

week. On Monday and Saturday, for instance, one reflects on the 'Joyful

Mysteries', namely The Annunciation of Gabriel to Mary (Luke 1:26-38);

The Visitation of Mary to Elizabeth (Luke 1:39-56) and so on. On Tuesday

and Thursday, we contemplate the 'Sorrowful Mysteries': The Agony of our

Lord in the Garden (Matthew 26:36-56), Our Lord is Scourged at the Pillar

(Matthew 27:26) and so it goes.

A

bead, then, is associated with, and triggers a particular prayer as well

as a cluster of biographical events in the lives of Jesus and Mary. These

disparate texts are in turn given coherence via the rosary. The recited

texts have agency in the world since they can

accomplish works of redemption in this world and the next. The texts also

mark the passing of time and remind one of what day of the week it is.

A

rosary, then, is a mini-textual 'factory', a physical site where texts

are generated and disseminated, floating to the next world and the ears

of God. Rather like /Xam stories which float in the air, these texts can

glide through time and space and have effects in this world and the next.

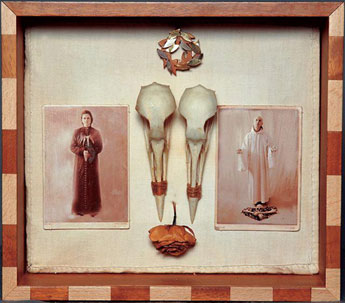

At points in the exhibition, this comparison is made explicit. In one

grouped display of boxes, we encounter a leopard spine inscribed with

the texts of the rosary. On either side, are photographs of Diä!kwain,

one of Lucy Lloyd's primary informants. The juxtaposition invites us to

compare the rosary as a set of textual practices with those of the /Xam.

The

juxtaposition is arresting and itself becomes a 'factory' of speculative

comparisons in which /Xam and Catholic practices are compared and defamiliarised.

What if the leopard's spine were to become the rosary? Imagine the rough

penitential work involved in reciting a whole cycle of the rosary! What

if we considered the rosary, not as an inanimate object, but rather treated

living objects as rosaries, using them from afar to generate texts of

meditation? Is it useful to think of the leopard as a type of rosary for

the /Xam? Did it unify a set of discrete and repeated texts (for instance,

about leopards and humans, hunting, predators, the porous relation of

humans, animals and gods) and so function as a usable archive?

The

/Xam often saw texts as objects that floated in the air, came with the

wind and carried within them the past and the future. The texts of the

rosary function in the same way: they are released into the next world,

and like all religious texts, collapse time. To contemplate on Jesus'

life is to enter, what one historian has aptly called the "apostolic

dream time" (Peel 155).

As

Skotnes herself has explained, this complex and layered comparison between

Christian and /Xam practice forms one of the important foundations in

her corpus:

The

exhibition hopes to create an arresting comparative exposition of rituals

and ideas that are at once central to /Xam cosmology and more broadly

Christian traditions, and set these against images from periods of global

and colonial conflict where, it contends, notions of sacrifice have enabled

violence and brutality. One of the aims of this project is to place /Xam

ideas within the global imagination - not that this has not already been

done in other ways - but here in a way that simultaneously highlights

the tragedy of the loss of culture and the strangeness of our own (western)

traditions and beliefs. ("Lamb of God")

Another

'instruction' we can, then, take with us is to read the exhibition as

a /Xam rosary. It is after all an exhibition made up of different 'joints'

or 'beads', each of which we must experience physically, each of which

we must contemplate on, each of which is a mystery and each of which (because

it is so multivalent) would render up a different narrative on any day

of the week. Like a rosary, the exhibition functions as the locus for

a set of texts. Many of these have 'floated' to us through time via the

agency of people like Diä!kwain and Lloyd and are held together productively

by the 'rosary' of the exhibition.

The Archive

At

several points in the exhibition, the archive created by Bleek and Lloyd

is invoked: sections of it are inscribed on one horse, images of rolled

up documents from the archive are included and individual pages and letters

written by Lloyd are reproduced. Indeed Lloyd herself appears in the exhibition,

dressed in a priest's robes.

The

idea of the archive has of course loomed large in recent academic thought

(Hamilton et al) and has become a strategy to contemplate reflexively

on disciplines in the humanities and social sciences. Archives are now

less sources of information to be mined for facts but are rather institutional

sites through which the politics of knowledge may be profitably analysed.

The term, often used with a capital 'A' has become a way of talking about

virtually any corpus of texts as a configuration of power (Stoler). In

relation to state-sanctioned collections of documents, debate has focused

on archives as sites for analyzing state craft and technologies of rule.

The nature of state power is then analysed through the systems of classification

that states use in their "paper empires" (quoted in Stoler 90);

the grid of intelligibility through which these operate; and the codified

fictions through which states authorise themselves.

The exhibition invokes the metaphor of the archive and so turns our attention

to these debates. However, it soon becomes apparent that this exhibition

is less interested in reading archives as configurations and grids of

power than of asking how these may be eluded. This tendency becomes apparent

if we turn to the biography of the horse skeletons. As the artist explained

to me, the idea for these emerged after she had unsuccessfully attempted

to prevent the State Library from claiming a depository copy of an art

book, Sounds from the Thinking Strings: A Visual, Literary and Archaeological

and Historical Interpretation of the Final Years of /Xam Life. Skotnes

maintained that the book was a work of art and so did not fall within

the scope of the deposit law. The State Library maintained it was a book.

After a protracted set of court cases, the Library won and claimed its

book. What type of book, Skotnes wondered, could one make that the library

couldn't claim? Could one make a book to evade the state with its extractive

demands and forms of classification?

| Next |